Delaying the Final Judgment (at Least in Patent Prosecution)

In prosecution of patent applications before the USPTO, an office action is an official letter sent by the USPTO. In it, an examining attorney lists any legal problems with the applicant’s patent, as well as with the application itself. It requires a written response that addresses each point of objection and/or rejection. in order for prosecution of the patent application to continue.

Office actions on the merits are either non-final or final. Non-final Office actions allow applicants to respond with amendments entered as a matter of right, and/or with arguments against the issued raised by the Examiner. Most importantly, filing of a response to a non-final Action removes the deadline for responding, with a new deadline imposed only when the Examiner acts again, such as by issuing another Office action.

“Final” Office actions (which really aren’t final in terms of concluding prosecution) impose more limitations on applicants. Although further amendments and/or arguments can be submitted, there are limitations on amendments (for example not allowing amendments that increase the total number of claims), and amendments cannot made be made as a matter of right. For example, the Examiner may deny entry of an amendment that would raise new issues. In addition, the filing of a response to a final Office action does not remove the deadline for taking further action. While the final action is pending (until the application is allowed, a notice of appeal is filed, or a Request for Continued Examination is filed) the clock continues to run for the applicant to take further steps to avoid abandonment of the application.

Usually, a first Office action in an application is a non-final action, while the second action is a final one. As stated in MPEP 706.07(a), “Second or any subsequent actions on the merits shall be final, except where the examiner introduces a new ground of rejection that is neither necessitated by applicant’s amendment of the claims, nor based on information submitted in an information disclosure statement filed” after the issuance of the first Office action. Given the limitations to applicant in responding to a final Office Action, it is to the applicant’s advantage to fall into the exception of MPEP 706.07(a) when claim amendments are made, so that a second non-final Action will be issued. Unfortunately, Examiners try to avoid issuing multiple consecutive non-final Office actions, since the Examiner does not get production credit for the second and subsequent non-final actions.

So how broad is the MPEP 706.07(a) exception in situations where the claims were amended in response to a previous (presumably non-final) Office action? In other words, when is a new ground of rejection in the next Action not “necessitated by applicant’s amendment of the claims”? Let’s consider four situations, encompassing all of the possible combinations of 1) whether the claim amendment broadened or narrowed the claim, and 2) whether the claim was previously indicated as allowable, as was rejected over prior art.

A word first on broadening and narrowing amendments. An amendment is considered broadening if it broadens any aspect of the claim (covers anything that was not previously covered by the claim), even if it narrows other aspects of the claim. See MPEP 1412.03(I) (“A claim of a reissue application enlarges the scope of the claims of the patent if it is broader in at least one respect, even though it may be narrower in other respects.”). Narrowing amendments do not broaden any aspect of the claim. (Amendments that do not affect the scope of a claim are thus also “narrowing” amendments under this definition.)

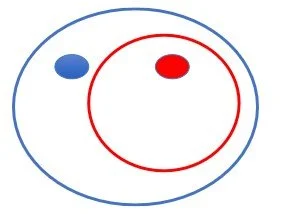

1. Narrowing claim amendment of a previously rejected claim

This situation is illustrated in Figure 1, where the blue line and blue dot represent respectively the claim scope prior to amendment and the prior art applied in the previous rejection, and the red line and the red dot represent respectively the amended claim scope (narrowing amendment) and the prior art applied in the new ground of rejection. This is the classic case of an amendment necessitating a new ground of rejection – after the first rejection the claim was narrowed (red line) to get around the previously-applied prior art (blue dot). So, the Examiner comes back with a new ground of rejection (red dot) for the narrower claim. If this is the only new ground of rejection the new Action can clearly be made final.

2. Broadening claim amendment of a previously rejected claim

This situation, illustrated in Figure 2, plays out in a similar way to the first one. The claim scope has been revised to distinguish the first prior art applied (blue dot), and a new ground of rejection (either one of the red dots) has been made to replace the applied prior art previously distinguished. If the new ground of rejection is in the broader part of the amended claim (rightmost red dot in Figure 2) the amendment clearly necessitated the new ground of rejection, since the new ground of rejection could not have been made prior to the amendment. But even if the new ground of rejection is within the claim prior to amendment (leftmost red dot in Figure 2) the situation is that of the Figure 1, discussed above, where the amendment to distinguish previously-applied prior art (blue dot) necessitated the new ground of rejection. As with the first case, this new ground of rejection does not prevent the second Action from being made final.

3. Broadening claim amendment of a previously allowable claim

Now things get interesting. What if the claim was previously allowable (not rejected on prior art grounds), was amended to now be broader, and a new ground of rejection is now imposed? This is the situation in Figure 3. Or rather it is two situations -- the red dot on the right represents a new ground of rejection in the scope brought into the claim by the broadening amendment, and the red dot on the left shows a new ground of rejection within the scope of the (previously) allowable claim. Let’s look at these in turn.

The rightmost red dot situation, where the new ground of rejection is fully within the part of the claim that has been enlarged beyond its original scope, is a clear case of a new ground of rejection necessitated by a claim amendment. This is so because the rejection could not have been made before the amendment, but now it can be.

So what of the other situation, the red dot on the left? Here the rejection could have been made before, but it wasn’t. Now the examiner has found a prior art rejection, and imposed it as a new ground of rejection, but you’ve got an argument (at least in the abstract) that the amendment didn’t necessitate the new ground of rejection – rather that ground of rejection was available to the examiner all along, and nothing about the amendment opened the door to that ground of rejection.

Good luck with that. While the argument may be sound in the abstract, it’s difficult to execute in practice. To pull it off you’d have to show (and convince the examiner or another decider) that the new ground of rejection touches no part of the scope added by the broadening amendment but is only applicable to the part of the broadened claim that was in its original scope. And, of course, in doing so you probably don’t want to make an admission that the new ground of rejection is valid, so you want to also preserve the argument that the new ground of rejection doesn’t cover the scope added by the amendment. On top of all that you have to dispute the finality of the new Action while dealing with a ticking clock. This is not a good position to be in.

Not that anyone should find themselves in this position in the first place. Broadening an allowable claim, without preserving the scope that has already been indicated as allowable over the prior art, is generally not something that should be done. You have a claim that’s indicated as allowable over the prior art, but you think that you might be able to get broader coverage? Keep the allowable claim, and add a new one with the broader scope. Or broaden the allowable claim, for instance by removing a clause not believed to be necessary for patentability, and then add that clause back in a new dependent claim. Just don’t put yourself in the situation shown in Fig. 3, where without preserving the allowable subject matter you open yourself up to a new, final rejection, by trying to broaden your coverage.

4. Narrowing claim amendment of a previously allowable claim

This situation, illustrated in Figure 4, is the only one that clearly wouldn’t justify making a final Action with a new ground of rejection. The new ground of rejection (red dot) is unequivocally within the original scope of claim, since the Examiner contends that it is within the scope of the narrowed amended claim, which by definition is fully within the scope of the original claim. There is no argument under this situation that the new ground of rejection is “necessitated by applicant’s amendment of the claims.”

Now that we are clear about how we need to approach amending claims, so as to avoid a second Action with a new ground of rejection being made final, let’s look at applying this in practice.

--

Why would anyone make a narrowing amendment to an allowable claim in the first place? Such a situation may occur when an independent claim is amended after a prior art rejection, while an allowable dependent claim was left as it was. If the Examiner enters a new ground of rejection against the previously allowable dependent claim, the final rejection would be improper if the amendment to the independent claim narrowed that claim.

That fact pattern occurred in a petition decision, In re Kachouh (Application 10/727,562, June 21, 2006). An amendment was made to independent claim 1 to distinguish prior art, and the Examiner issued a final Action including a new ground of rejection which included dependent claims 11 and 12, which were among the claims previously indicated as allowable subject. The petition was decided in the Applicant’s favor on the basis that the dependent claims should have still been allowable, as dependent from intermediate claims that were still indicated as allowable, but an examination of the claim amendment at issue is still instructive regarding how to make claim amendments so as to make clear that the amendment is narrowing in scope.

The invention in Kachouh involved a car door lock, and claim 1 was amended in response to the first Action as follows (added language is underlined, and deleted language is struck through, as is required by 37 CFR 1.121(c)(2)):

1. (Currently Amended) Motor vehicle door lock with latching elements comprising:

a latch;

a ratchet; and

a lock mechanism, the lock mechanism further comprising a drive having a drive motor and an actuating element,

wherein the ratchet is raisable by the drive via the actuation element, the ratchet being positioned so that motion of the drive is blocked by the ratchet, viewed in a kinematic chain from the drive motor to the actuating element, engages the drive so as to block it at a location before the actuating element and wherein the rachet blocks the drive without directly engaging the actuating element.

Setting aside some problematic language in the claim (the inconsistent(?) recitation of both “latching elements” and a “latch,” of both a “door lock” and a “lock mechanism,” and of both “an actuating element” and “the actuating element”; and the potentially ambiguous (and thus possibly indefinite) “it” in the last clause), does this amendment narrow the scope of the claim? Recall that an amendment broadening if it broadens any aspect of the claim (covers anything that was not previously covered by the claim), even if it narrows other aspects of the claim. Here language has been added, but other language has been deleted. Aspects of the claim have been narrowed, but it’s not clear on its face whether other aspects of the claim have been broadened.

This amendment could have been more clearly made as a narrowing amendment by rewriting it to avoid the deletion of any language:

Now the amendment only adds language, and clearly narrows the claim’s scope. An applicant would have a good case that a second (or subsequent) Action should not be made final if a new ground of rejection was made a previously-indicated allowable claim that depended from this amended claim (or if this claim itself had previously been allowed).

The situations where one can successfully contend that a new ground of rejection of an amended claim was “not necessitated by the amendment” are rare, but it is useful to recognize them and be ready to push back against the finality of the rejection when appropriate. And it is good to approach claim amendments with the goal of making a narrowing amendment clear, when it is made in the situation where some claims are indicated as allowable, in the hopes of making the examiner issue another non-final Action if he or she wants to issue a new ground of rejection for the allowable claims.

At Renner Otto, the oldest intellectual property firm in Cleveland, we specialize in assisting our clients as they develop efficient Intellectual Property strategies that are tailored to their business’s needs. Our attorneys are knowledgeable on a wide range of domestic and international IP issues, and we partner with Firms around the world to better serve our clients.

Someone from the Renner Otto team would be happy to discuss this topic or any related Intellectual Property matters. Contact us for a complimentary consultation to see how we can help your business move your innovation forward.

The attorneys at Renner Otto strive to be authorities in all matters concerning the ever-evolving landscape of Intellectual Property; however, the information provided on our website is not intended to be legal advice, nor does it create an attorney-client relationship.